Refractive

March 2021

by Liz Hillman

Editorial Co-Director

Corneal ectasia after laser vision correction was first reported in 1998 by Theo Seiler, MD, PhD,1 and since then, preop screening and treatment parameters have improved to help avoid such a complication. The incidence of post-LASIK ectasia (as it is commonly referred to though ectasia can occur with other refractive and corneal procedures) is not officially known. Research from the early 2000s puts it at 0.2–0.6%.2,3,4 A retrospective review in 2018 of 30,167 eyes that had LASIK (16,732 patients) from 2007–2015 with follow-up between 2 and 8 years saw an ectasia incidence of 0.033% over this timeframe.5

“Over the 20+ years of experience since [the first LASIK cases], we’ve gained a lot of knowledge about both the corneal anatomy and the impact of LASIK on the cornea,” said Evan Schoenberg, MD. “Unfortunately, some of that knowledge is from experience because some patients have developed ectasia. Along the way we’ve also developed better diagnostic devices. I think the playing field has changed a lot since the early days of LASIK, and it’s a combination of better diagnostics and better awareness.”

Source: Evan Schoenberg, MD

Maria Jose Cosentino, MD, had a similar viewpoint on the reason for decreasing post-refractive surgery ectasia incidence.

“Nowadays the incidence of corneal ectasia after LASIK is decreasing due to, on one hand, the existence of risk-calculation indices (the new and updated traditional ones) and on the other hand, the new alternatives for the refractive treatment of moderate and high myopias that prevent the weakening of the cornea,” she said.

Dr. Schoenberg said he thinks the biggest change to further reducing ectasia risk has been awareness of the risk factors for corneal ectasia and the development of scoring systems for those risk factors.

“I like the Randleman ectasia score. I don’t think it says everything about the risk for ectasia, but it nicely summarizes some of the basic factors that we look at,” he said, noting the variables of the Randleman score: topographic pattern, predicted residual stromal bed (RSB) thickness, age, preoperative corneal thickness (CT), and manifest refraction spherical equivalent (MRSE). “It’s a useful summary of the basics you want to look at, but it’s not the only thing you want to look at.

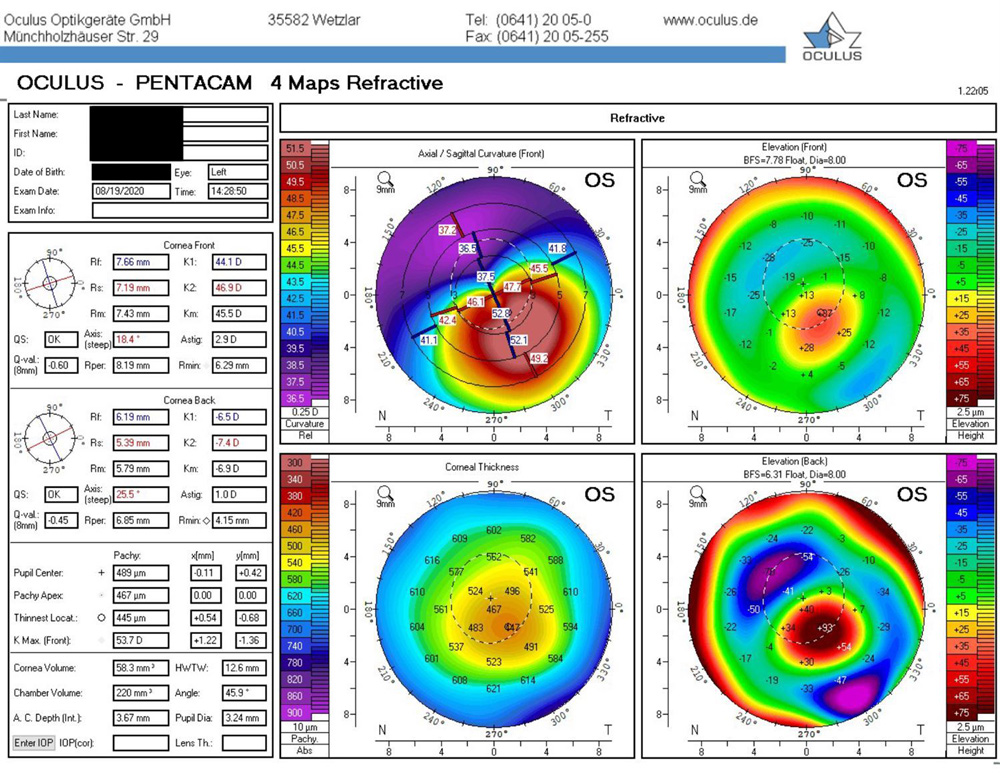

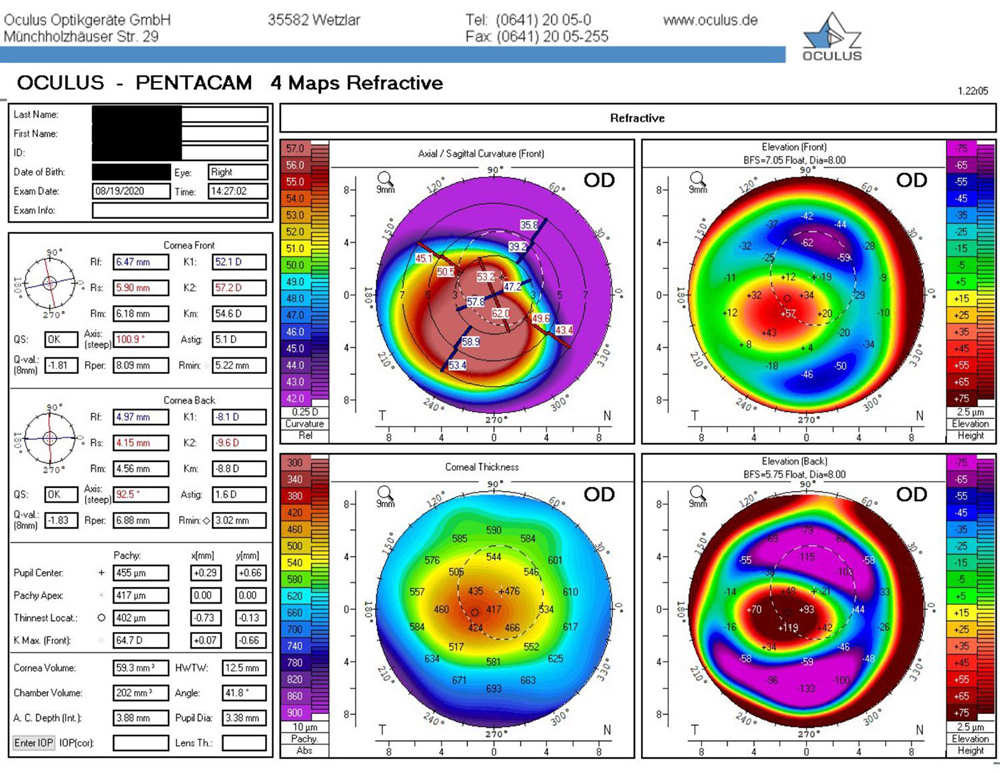

“The addition of imaging systems like Pentacam [Oculus] and Galilei [Ziemer] that provide information on the posterior cornea is the other widespread revolution in understanding high-risk patients for LASIK. More recently the addition of epithelial mapping has been another valuable tool,” Dr. Schoenberg said, adding that he doesn’t have much experience with epithelial mapping yet. “Another tool that I don’t use routinely but I have in my arsenal is genetic testing. … We tend to think that most patients who get post-LASIK ectasia after successful surgery are probably patients who would have had some degree of subclinical or clinical keratoconus anyway.”

Dr. Cosentino brought up irregular corneal topography as an important risk factor to watch out for.

“Randleman et al. reported corneal topographic irregularity in 50% of the patients with corneal ectasia,” she said.6

Candidacy for a refractive procedure is more than just preop testing. Dr. Schoenberg emphasized the safe ranges to which the cornea can be altered. Dr. Cosentino also mentioned the operative risk factors—a thin preoperative cornea and/or thick LASIK flap.

“In moderate myopes I start talking about and in higher myopes I recommend an implantable collamer lens,” Dr. Schoenberg said. “Rather than recommending a –9 LASIK, which is an on-label treatment, I would typically talk to that patient about an implantable collamer lens. That might be the shift in thinking that can change the [incidence of ectasia].”

Dr. Cosentino also addressed percent tissue altered (PTA) as a factor to look at, with 40% PTA or higher being a risk factor for post-LASIK ectasia.

“Marcony Santhiago, MD, proposed a metric for calculating the ectasia risk in patients who have undergone the LASIK procedure.7 This metric can be expressed in terms of the following equation: PTA=(FT+AD)/CCT,” Dr. Cosentino said.

As a cornea and refractive keratoconus specialist, Dr. Schoenberg gets a referral for ectasia after refractive surgery every couple of weeks, but he said most of these cases are 10-plus years postop. He said when he has the opportunity to review the preop testing on these patients with a current knowledge base, sometimes they are patients he would not recommend for surgery today. “In one case, the preoperative topography had a huge difference. It was a 3 D inferior vs. superior difference on the map. … The map that was sent to me was printed in 1 D steps. It matters because when you do big steps, everything smooths out,” he said, explaining the importance of using a scale with a high enough granularity to detect abnormalities.

Dr. Schoenberg said the long-term safety data on refractive surgery offers confidence to patients, as well as the fact that there are treatments should the rare complication of ectasia arise postop.

“I don’t minimize its risk but I do instill confidence about what we’re looking at before surgery and what we can do after surgery because if we have this condition that is unstoppable and scary, that’s very different from a condition that can be controlled and managed,” he said, explaining that crosslinking can effectively stop ectasia before it poses a significant problem.

About the physicians

Maria Jose Cosentino, MD

Instituto de la Vision

University of Buenos Aires

Buenos Aires, Argentina

Evan Schoenberg, MD

Georgia Eye Partners

Atlanta, Georgia

Relevant disclosures

Cosentino: None

Schoenberg: None

References

- Seiler T, Quurke AW. Iatrogenic keratectasia after LASIK in a case of forme fruste keratoconus. J Cataract Refract Surg. 1998;24:1007–1009.

- Randleman JB, et al. Risk factors and prognosis for corneal ectasia after LASIK. Ophthalmology. 2003;110:267–275.

- Rad AS, et al. Progressive keratectasia after laser in situ keratomileusis. J Refract Surg. 2004;20:S718–S722.

- Pallikaris IG, et al. Corneal ectasia induced by laser in situ keratomileusis. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2001;27:1796–1802.

- Bohac M, et al. Incidence and clinical characteristics of post LASIK ectasia: A review of over 30,000 LASIK cases. Semin Ophthalmol. 2018;33:869–877.

- Randleman JB, et al. Validation of the Ectasia Risk Score System for preoperative laser in situ keratomileusis screening. Am J Ophthalmol. 2008;145:813–818.

- Santhiago MR, et al. Association between the percent tissue altered and post-laser in situ keratomileusis ectasia in eyes with normal preoperative topography. Am J Ophthalmol. 2014;158:87–95.

Contact

Cosentino: majose.cosentino@icloud.com

Schoenberg: evan.schoenberg@gaeyepartners.com