Cornea: Cornea editor’s corner of the world

July 2014

by Ellen Stodola

EyeWorld Staff Writer

Adenovirus infections are one of the dreaded entities seen in clinical practice because of their extremely contagious nature. Differentiating the red eye from a bacterial conjunctivitis can also be a challenge. The acute treatment of adenoviral conjunctivitis remains mostly supportive, although a newer topical antiviral gel, which is not specifically FDA approved for this indication, might be an option for some patients. The role of steroids and timing of the topical application remain controversial. Persisting and visually significant subepithelial infiltrates are a frustrating sequelae of adenoviral infections. Topical steroids and cyclosporine and phototherapeutic keratectomy (PTK) are some options for management, but the infiltrates are still prone to frequent recurrence.

This month’s “Cornea editor’s corner of the world” focuses on the diagnosis and treatment of adenoviral conjunctivitis and the management of associated sequelae. Bennie Jeng, MD, and Francis Mah, MD, discuss their experience with adenovirus spot testing, diagnostic clinical features, timing of topical steroid use, and management of subepithelial infiltrates.

—Clara C. Chan, MD, cornea editor

Adenoviral conjunctivitis can be tricky for practitioners because of the challenges associated with diagnosing and treating. Patients often come in with non-specific symptoms, so differentiating between bacterial and viral infections, as well as finding a treatment to manage the issue, is vital. Bennie H. Jeng, MD, Baltimore, and Francis Mah, MD, La Jolla, Calif., discussed identifying and treating these patients.

Clinic spot testing

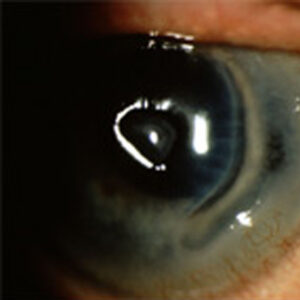

Source: Francis Mah, MD

Clinic spot testing kits, like the RPS Adeno Detector (Rapid Pathogen Screening, Sarasota, Fla.), can be helpful in identifying patients.

Dr. Jeng said that the tests are generally useful, both for primary care physicians and for ophthalmologists. The tests can be helpful because of their sensitivity, rendering them an effective way to make a diagnosis of viral infection so antibiotics do not have to be prescribed.

Dr. Mah finds these tests helpful, especially because patients often come in with red eyes that are very non-specific.

“At least it helps to confirm or eliminate viral conjunctivitis as a cause,” he said.

Identifying and differentiating

“One of the key features is that it’s a follicular conjunctivitis. You also typically get a preauricular node, which is a sensitive new nodule in front of the ear,” Dr. Mah said. “It’s typically adenovirus or herpes virus that causes that from a viral etiology,” he said.

Generally, viral conjunctivitis will present with a thinner, more tearful discharge, whereas bacterial conjunctivitis is going to be a thicker, goopier discharge, Dr. Mah said.

The main question, Dr. Jeng said, is if it is viral or bacterial. “It’s often clear based on the history if it’s infectious or not.” Unfortunately, the symptoms are sometimes non-specific, including itching, tearing, and watery discharge. “In addition, we generally try to associate watery discharge with viral and more yellow/green discharge with bacterial, but it can be vice versa on different occasions,” he said.

Treatment

“For adenoviral conjunctivitis, I don’t think that there’s a good treatment,” Dr. Jeng said. Supportive care is the main way to get the patient through the condition, he said.

“In general, there is no role for steroids in treating this.” Steroids prolong viral shedding, so they are good for the patient because the symptoms improve but they are bad for everyone else because the patient is contagious for longer. However, Dr. Jeng did note that there might be a role for steroids in severe cases that render it difficult for patients to function.

“Right now there is no antiviral that’s FDA approved for adenovirus, so a lot of it is prevention of spreading because it is very contagious, and supportive care until the self-limiting infection passes,” Dr. Mah said. Telling patients to wash their hands, keep their hands away from the eyes and tears, change their pillowcases, and generally practice good hygiene can help stop the spread.

Off label, physicians could prescribe commercial topical ganciclovir gel (Zirgan, Bausch + Lomb, Bridgewater, N.J.), Dr. Mah said. Several clinical studies show there is some efficacy with this in certain serotypes of adenovirus. He likes to have a discussion with patients to let them know it is not FDA approved, but there is truly nothing else available, so they may want to try it. Dr. Mah added that there are new studies looking at antivirals from Alcon (Fort Worth, Texas), Allergan (Irvine, Calif.), and ForSight Labs (Menlo Park, Calif.).

Steroids can be helpful in inflamed eyes if they have membranes, Dr. Mah said. “You do have to be careful because the steroids can also increase the viral spread by increasing shedding and length of time before shedding ends.” Using lose dose and low frequency steroids can be helpful, and Dr. Mah said he uses these for very severe cases.

Management of subepithelial infiltrates

If Dr. Mah sees subepithelial infiltrates initially and they do not seem to be that visually or symptomatically impactful, he will have a discussion with the patient and recommend artificial tears. If they are visually significant, however, he may choose to use lower potency steroids, like Lotemax (loteprednol, Bausch + Lomb) or flurometholone. In persistent cases, where he is concerned about the long-term use of steroids, he might use topical cyclosporine, epithelial debridement, or even phototherapeutic keratectomy (PTK).

Dr. Jeng said for the most part, especially if the symptoms are not severe and the infiltrates are in the periphery, the treatment for this is nothing. “What a lot of physicians do that ends up getting the patients in trouble is treating any subepithelial infiltrates with steroids because steroids will make these things go away,” he said. “The problem is if you start them on steroids, it can be very difficult to get them off; every time you taper them off, it comes right back.” He said it would be better to let the issue run its course in most cases. However, he would treat subepithelial infiltrates if there were a lot of them or if they were over the center of the cornea, which could lead to scarring or a decrease in vision.

Number of patients

Dr. Jeng said that he sees many patients with this condition. Usually, they have been tapered on and off steroids several times. “I’ve had patients who have been on steroids for seven years before they see me.” Generally in these cases, Dr. Jeng said the ophthalmologist has been doing a good job managing the condition, but cannot get the patient off steroids.

Dr. Mah said that working in Pittsburgh, he did not see many cases of adenovirus conjunctivitis, but in San Diego, he saw a dozen patients last year in a 4-month period. “There definitely seems to be a season to it,” he said. He added that the diagnostics are improving, and hopefully one day there will be a therapy.

Editors’ note

Dr. Jeng has no financial interests related to his comments. Dr. Mah has financial interests with Alcon, Allergan, Bausch + Lomb, and ForSight Labs.

Contact information

Jeng: BJeng@som.umaryland.edu

Mah: Mah.Francis@scrippshealth.org