For a more recent article on this topic, see “Review of ‘Diffuse lamellar keratitis after LASIK with low-energy femtosecond laser.’”

Refractive Surgery

June 2008

by Michelle Dalton

EyeWorld Contributing Editor

Differentiating between the stages is the only way to offer effective treatment, clinicians say

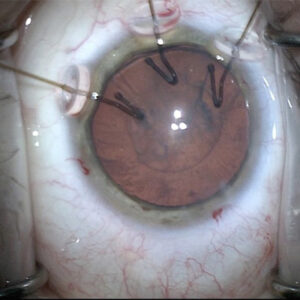

Diffuse lamellar keratitis (DLK) results in the accumulation of inflammatory cells in the interface between the LASIK flap and corneal stroma, and can be one of the most serious complications of LASIK if not treated quickly and properly.

“DLK is a cellular reaction that almost always presents in the first 24 hours after surgery,” said Jason Stahl, M.D., assistant clinical professor of ophthalmology, Kansas University Medical Center, Kansas City, and Durrie Vision, Overland Park, Kan. Frequently, presentation at the periphery is most dominant, he said. “You can have epithelial surface abnormalities you might think are DLK, but when you look at the epithelium, it’s not in the interface,” he said. “You need to make sure it is DLK, not meibomian gland debris, before treating.”

Although it has a relatively low incidence rate (somewhere around one in 50 for mild cases), the etiology of DLK is still not completely understood, said Parag A. Majmudar, M.D., associate professor of ophthalmology, Rush Medical Center, Chicago. “There may be ‘epidemic’ DLK caused by external or environmental toxins or patients may be predisposed toward developing it, but sometimes there may be no reason for it,” he said. About 10 years ago, Richard L. Lindstrom, M.D., and colleagues at Minnesota Eye stratified the severity of DLK into four stages, Dr. Majmudar said. “Early DLK, characterized as stage 1 or stage 2, occurs with the accumulation of inflammatory white blood cells in the interface, either in a peripheral pattern or a diffuse pattern,” Dr. Majmudar said.

The first two stages will rarely affect vision, said Perry S. Binder, M.D., co-founder, Gordon-Binder-Weiss Vision Institute, San Diego. By stage 3, the cells will be relatively dense and clumped in the interface. Stage 4 involves clumping and a “severe decrease” in vision, he said. Stages 3 and 4 should be treated by lifting the flap and treating hourly with topical 1% prednisolone, he said. “In short, DLK is the corneal equivalent of toxic anterior segment syndrome [TASS],” said Daniel G. Dawson, M.D., formerly with Emory Eye Center, Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta.

DLK can present late, any time there is trauma to the epithelial defect, Dr. Binder said. “DLK can present after an enhancement surgery as well,” he said. Performing an enhancement with surface ablation instead of LASIK “may or may not prevent DLK from occurring.”

Interface fluid syndrome or DLK?

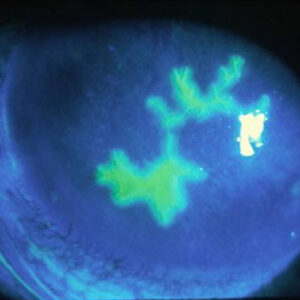

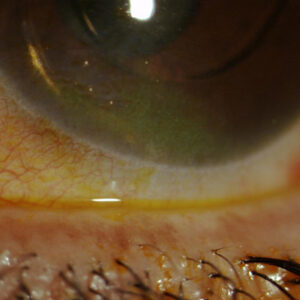

A LASIK complication that can be confused with DLK is interface fluid syndrome (IFS). IFS is a flap-related complication caused by corneal edema—from high IOP or endothelial cell dysfunction—in eyes that have had LASIK. Last year, Dr. Dawson and colleagues at the Emory Eye Center published their research results on the pathogenesis of this condition and organized the severity of IFS into three stages: mild (stage 1)—thickening of interface wound with minimal haze; moderate (stage 2)—thickening of the interface wound with frank haze; and severe (stage 3)—development of a pocket of interface fluid. Patients with IFS typically complain of decreased vision about 1 to 2 weeks after initial surgery, but the presentation can be as late as months to years after the surgery, Dr. Dawson said. “Clinically, it can be easy to confuse stage 2 IFS with stage 2 to 3 DLK,” he said. “A more granular, windswept ‘Sands of Sahara Syndrome’ presentation tends to occur with DLK, whereas the excess fluid in IFS causes a diffuse smudgy kind of grayish haze in the entire central and paracentral interface wound.”

Additionally, Dr. Dawson said IFS is commonly caused by topical steroid-induced ocular hypertension and does not respond to steroids. It will, however, resolve with the discontinuation of topical steroids and/or IOP-lowering drops. “Treatment for IFS is completely the opposite from DLK—steroids suppress the inflammatory response in DLK, but do not particularly help remove the excess fluid from IFS, or it can make the condition worse if it raises the IOP,” he said. “If steroid-induced ocular hypertension is the cause, get the patient off steroids and onto pressure-lowering drops.”

“Interestingly, if the IFS is from Fuchs’ endothelial cell dystrophy or another endothelial cell problem, steroids probably won’t do much to treat the condition in the long term, but may temporarily tighten the endothelial cell macular occludens tight junctions, causing transient, fluctuating episodes of improvement, which only confuses clinical diagnosis,” Dr. Dawson said. “The main message to understand is that IFS is not due to inflammatory cells or an inflammatory response in the interface wound like DLK; it is due to excess fluid that causes keratocytes to undergo hydropic degeneration, which clinically appears as a smudgy diffuse interface haze.”

Dr. Stahl agreed, saying, “Traditional DLK is going to respond early to steroids. If the patient presents later, you have to consider that something else is going on and steroids may not be appropriate.”

“The risk with any treatment is that you don’t want to raise the IOP,” Dr. Binder said. “When the pressure rises, the endothelium can’t handle the fluid pressure, and it leaks into the interface. You think the condition is worsening, it looks hazier, so you start pouring on more steroids. You’re not able to obtain accurate pressure measurements. In those cases that occur 7 to 14 days later, you have to rule out steroid-induced pressure rise.”

Dr. Dawson pointed out the difficulties of IFS, saying, “The toughest part of IFS is that some patients initially do have DLK, which is treated successfully with topical steroids. Unfortunately, by the time the patient comes back in for a follow-up visit 1 to 2 weeks later, the IOP increases from the topical steroids in patients who are steroid responders.”

“If the high IOP is not picked up (e.g. IOP is measured only centrally), this make the ophthalmologist think that the DLK is unresolved or getting worse, so they increase the dosage of steroid drops already being used when in actuality they should be stopping them”, Dr. Dawson said continued. “In fact, there are a few case reports in the literature describing this exact situation and sometimes it was corrected too late as severe or end-stage secondary open angle glaucomatous damage occurred.”

The DLK/IOP link

The treatment of DLK with steroids may predispose certain patients toward developing a sterod-induced rise in IOP, Dr. Majmudar said. “Certain patients will be treated for DLK and then develop characteristics of IFS, or you may have a situation where a patient presents with interface haze and is treated for DLK, whether it’s true DLK or not, and that sets up a vicious cycle. It’s a common mistake that can be made—the patient has stromal keratitis, not true DLK.”

The difference between a pressure-induced keratitis and DLK is that the latter is inflammatory “and will have a granular appearance. If you look at the interface and see a grainy or sandy infiltrate, that’s DLK,” he said. “When you look at pressure-induced keratitis there may be interface ‘haze,’ but it’s not granular. It looks more like frosted glass.”

If the IOP increases while the patient is on steroids for DLK, “there is some compromise of endothelial pump function egressing fluid in the cornea that will find the interface,” Dr. Stahl said. “The edema looks similar to DLK, but it’s imperative to stop the steroids and start glaucoma medications to resolve the inflammation.”

Pressure-induced keratitis, by definition, involves high pressure. When the patient starts steroids for DLK, a pressure spike results. “People can lose their vision” in the most serious cases, Dr. Majmudar said. He advised surgeons not to take pressure readings on the center of the flap, “but on the periphery where the true pressure will be found. You maybe get a 10 to 20 mm Hg reading in the middle if you are sensing the IOP in the fluid pocket, but the pressure measured peripherally might be as high as 38 or 40 mm Hg.”

Additionally, DLK presenting weeks after LASIK is unlikely, he said. “At that point, it’s usually pressure-induced keratitis.”

Stopping steroids and putting the patient on glaucoma drops will usually be all that’s needed to return the patient’s pressure to normal levels. “Once the IOP comes down, vision usually returns,” he said.

IntraLase results

Recently, reports from a Spanish clinic noted DLK seemed to occur more frequently after LASIK with the IntraLase 15 kHz femtosecond laser (Advanced Medical Optics, AMO, Santa Ana, Calif.) than when LASIK was performed with a Moria M2 microkeratome (Doylestown, Pa.).1 At first read, results seem to contradict what others have found. “Cases of DLK after IntraLase have a little different etiology than with a regular microkeratome,” Dr. Stahl said. “Early on, what we would call DLK looked like granular cells in the interface, but it didn’t respond to steroids. It slowly went away, didn’t progress, didn’t change. We felt it might have been swollen keratocytes in the interface produced from the more traumatic flap lift. But as the IntraLase has become faster, we’ve been able to greatly reduce the energy needed to make the flap. I can’t remember the last time I had to treat DLK.”

Dr. Binder added that it is not unusual to see an increase in DLK when people initially switch from a microkeratome to the IntraLase. “But if you’re seeing cells in the visual axis, it’s not the laser, it’s something in the system. The IntraLase introduced new energy, and sometimes we see cells in the periphery, but it’s not diffuse or DLK,” Dr. Binder said. “It’s primarily associated with new users and new energy settings. When you cut down on the energy used, you just don’t see it anymore.”

The bottom line for Dr. Binder? “If you’re seeing cells in the interface in the center, and you’ve just switched from one platform to another, it’s not the laser. It’s likely something else.”

Because the Da Vinci femtosecond laser (Ziemer Ophthalmic Systems, Port, Switzerland) cuts simultaneously with the center, Dr. Binder expects even new users to have low complication rates.

Final advice

Dr. Majmudar offers these pearls: “When treating DLK, don’t forget about the pressure, and also don’t forget about potential infection, from either fungal, bacterial, or atypical sources. Any of these insults can cause DLK. If you lift the flap, make sure you take cultures; there can be a serious poor outcome if you miss it. Note that vigorous scarping of the stromal bed is to be discouraged as the already necrotic cornea may lose even more volume, resulting in a hyperopic shift. Above all else, treat aggressively with antibiotics as dictated by the cultures.”

His preferred treatment regimen is a Medrol (methylprednisolone, Pfizer, New York) pack, tapering over six days. “Oral prednisolone is a little much for me at the outset, unless the inflammation is severe and then it may need to be described in high doses. I usually reserve its use for when the patient doesn’t respond,” he said. He also noted methozone has “virtually inconsequential side effects,” although he warns all patients that side effects may occur.

When Dr. Stahl’s patients don’t respond to steroids, “I have a low threshold for lifting the flap and irrigating the interface,” he said. “Without a doubt, flap lifting is needed at stage 3; if you lift and irrigate then you’ll prevent progression to stage 4.”

He did caution surgeons to remember that flap lifting and irrigation “maybe not be indicated for stage 4 DLK because it sometimes removes stromal volume,” and steroid therapy with observation may be the best treatment.

Editor’s note

Dr. Binder has financial interests with Advanced Medical Optics (Santa Ana, Calif.)). Drs. Stahl, Majmudar, and Dawson have no financial interests related to their comments.

Contact Information

Binder: 858-455-6800, Garrett23@aol.com

Dawson: 770-891-0425, Daniel.g.dawson@gmail.com

Majmudar: 800-8-CORNEA, pamajmudar@chicagocornea.com

Stahl: 913-491-3330, jstahl@durrievision.com

References

- Gil-Cazorla R, Teus MA, de Benito-Llopis L, Fuentes R. Incidence of diffuse lamellar keratitis after laser in situ keratomileusis associated with the IntraLase 15 kHz femtosecond laser and Moria M2 microkeratome. J Cataract Refract Surg 2008; 34:28–31.