Cover Feature: Allergy

March 2007

by Vanessa Caceres

EyeWorld Contributing Editor

Ophthalmologists must navigate through uncharted areas when they treat their pregnant patients.

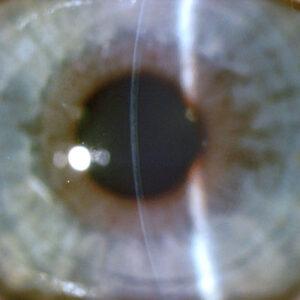

Source: Christopher J. Rapuano, M.D.

“My general rule of thumb in patients who are pregnant is to use the least amount of medication possible, even if I think the medications are safe,” said Christopher J. Rapuano, M.D., professor of ophthalmology, Jefferson Medical College of Thomas Jefferson University, and co-director, Cornea Service, Wills Eye Institute, Philadelphia.

“My second rule of thumb is to call the obstetrician and check with him on medications I think the patient needs to be on,” Dr. Rapuano said.

Practitioners said they would prefer to avoid the medicolegal risks that would accompany a child born with defects or other problems, which might cause a patient to wonder if the ophthalmic medication she used during pregnancy led to the child’s problem.

Practitioners generally follow the same guidelines while the patient is nursing, although they said they do not need to adhere as strictly to them. Although there is a dearth of research on the effects of ophthalmic medications during pregnancy, physicians take a cautious approach instead of waiting for such studies to be done.

Food and Drug Administration medication safety categories

A. Safety established using human studies

B. Presumed safety based on animal studies

C. Uncertain safety; no human studies; animal studies show adverse effect

D. Unsafe; evidence of risk that in certain clinical circumstances may be justifiable

X. Highly unsafe

Source: Douglas J. Rhee, MD; Food and Drug Administration

“These studies are hard to do, and they’re risky,” Dr. Rapuano said. “An animal study may or may not translate perfectly to humans. And these studies are not cost effective” because pregnant patients make up such a small portion of the population.

Below are some treatment approaches that ophthalmologists use with their pregnant patients who wear contacts or have dry eye, allergies, glaucoma, corneal infections, and other conditions.

Contacts and refractive surgery

Corneal thickness, curvature, and sensitivity as well as tear composition can all change during pregnancy, said Elizabeth A. Davis, M.D., Bloomington, Minn., who co-authored a chapter on pregnancy and the eye for the book Principles and Practices of Ophthalmology. For this reason, pregnant patients who wear contact lenses may find their contacts do not always fit properly, she said, or their contacts may feel greasier because of an increased level of lysozyme in the tear film, she said.

If these patients want to opt for refractive surgery because their contacts are uncomfortable, they have to think again, Dr. Davis said.

“We don’t do refractive surgery in pregnant women,” she said. “We recommend patients wait three months after giving birth and/or breastfeeding because of all sorts of hormonal changes that can change the refractive error.” Between the changes in refractive error that pregnancy can cause—which could lead surgeons to treat an inaccurate refractive error—and the unknown risks of any medications patients may take in conjunction with refractive surgery, waiting is a safer option, Dr. Davis said.

Dry eye and allergies

Dry eye can be an issue in pregnant patients who wear contact lenses and in those who experience nausea and vomiting, said John D. Sheppard, M.D., professor of ophthalmology, microbiology, and immunology, Eastern Virginia Medical School, Norfolk. The nausea and vomiting lead to dehydration, which can lead to drier eyes, he said. Certain medications that patients may take to inhibit nausea can also contribute to dry eye, he said. Practitioners seem to agree that artificial tear drops are a safe treatment option to lubricate the eyes. Another easy solution is asking patients to reduce contact lens wear or not wear them at all.

Beyond those easier steps, everyone has different ideas.

Dr. Sheppard said he “leans more toward the natural route” to treat pregnant dry-eye patients. This includes supplements such as fish oil, flaxseed oil, and black currant seed oil. Preliminary research and anecdotal evidence shows that omega-3 acids found in these supplements can help the ocular surface.

He uses silicone or plastic punctal plugs as well, an option that Dr. Davis also thinks is reasonable. “Punctal plugs and lubricant drops would be the mainstay of my treatment,” she said.

Restasis (cyclosporine ophthalmic emulsion 0.05%, Allergan, Irvine, Calif.), which is frequently used now to treat dry eye, may or may not be a good option for pregnant patients, physicians said.

“The use of Restasis is not contraindicated,” Dr. Sheppard said. “I have no problems treating pregnant patients with Restasis.” He said Restasis has an added benefit: helping to control ocular allergies.

However, “I’d take the patient off the Restasis, not because I think it’s unsafe but because it is cyclosporine and as far as I know, it’s not been tested [with pregnant women],” Dr. Rapuano said.

If the patient has severe dry eye, Dr. Sheppard is also comfortable using Lotemax (loteprednol etabonate ophthalmic suspension 0.5%, Bausch & Lomb, Rochester, N.Y.).

With seasonal allergies, Dr. Sheppard will use Restasis and drops such as Elestat (epinastine hydrocholoride 0.05%, Inspire Pharmaceuticals, Durham, N.C.) and Patanol (olopatadine hydrocholoride 0.1%, Alcon, Fort Worth, Texas). Still, he avoids oral antihistamines or antihistamines with a decongestant component. “With the systemic effects, we’re not 100 percent sure they’re safe for the fetus,” he said.

Patients who wear contact lenses and have seasonal allergies may find their symptoms more manageable if they avoid their contacts for awhile, Dr. Sheppard said.

Using the lowest amount of drops necessary and encouraging patients with allergies to use cool compresses are other possible approaches, Dr. Davis said. “If they’re miserable, I say it’s OK” to use drops for ocular allergies, Dr. Rapuano said. Still, he tries to keep their use to a minimum during pregnancy.

Dr. Rapuano also teaches his patients to perform digital punctal occlusion before they administer a drop and at least 60 seconds after they put a drop in.

“This significantly decreases the amount of the drop that gets into the nose and the bloodstream,” he said. “It keeps the medication more localized.”

Unusual situations

Dr. Rapuano said dilating drops are safe to occasionally use if it’s an urgent situation—a patient experiencing flashers and floaters, for example. If it is a routine examination, he advises the patient to wait until she has had the baby.

Even though practitioners generally prefer to avoid medications for pregnant patients, a corneal infection requires treatment, Dr. Davis said.

There are certain drops that are safer,” she said. “Erythromycin and polymixin B appear to be the safest antibiotics,” she said. “They’re not as broad spectrum as the fourth-generation fluoroquinolones, but I’d start with those and see if they’ll treat the problem.”

A corneal infection is another good situation in which to consult the obstetrician about the treatment plan, Dr. Sheppard said.

Low-dose steroid drops are usually safe during pregnancy in patients such as those who’ve had a corneal transplant and are on anti-rejection steroids, Dr. Rapuano said. However, he said he generally stops the use of antiviral medications such as Valtrex (valacylovir, GlaxoSmithKline, United Kingdom) in patients with herpes.

EyeWorld factoid:

Allergies have a genetic component. If only one parent has allergies of any type, changes are 1 in 3 that each child will have an allergy. If both parents have allergies, it is much more likely (7 in 10) that their children will have allergies.

Source: Asthma and Allergy Foundation of America

Glaucoma medication risks

For glaucoma patients, one positive aspect is that IOP tends to decrease naturally during pregnancy, said Douglas J. Rhee, M.D., assistant professor of ophthalmology, Department of Ophthalmology, Glaucoma Section, Massachusetts Eye & Ear Infirmary, Boston.

He cites previous studies that have been done in this area. He also did some research regarding pregnancy and the eye for the Ophthalmic Drug Guide, a book he co-authored that was published this year. Beyond the IOP advantage, he said that glaucoma specialists are especially cautious in their treatment of pregnant patients because of the unknown effects of glaucoma medications.

“All glaucoma medications have the potential to cause fetal and embryonic harm,” he said. “It’s not a well-studied area.” In fact, most glaucoma medications are classified in category C of the Food and Drug Administration’s safety categories; this means the drugs have an uncertain safety profile, there have been no human studies, and animal studies may show an adverse effect.

Two exceptions to the risks from glaucoma medications: brimonidine is category B and reasonable to offer up to one month before delivery and oral acetazolaminde was reported safe in a case series for the treatment of intracranial hypertension, published in 2005 in the American Journal of Ophthalmology. Still, the series only involved 100 patients, Dr. Rhee said. Plus, “acetazolamide during late pregnancy has been associated with renal tubular acidosis in the newborn and may have potential teratogenic effects if administered during the first 12 weeks of fetal development,” Dr. Rhee said, citing a 2001 study from Survey of Ophthalmology.

Amtimetabolites such as 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) and mitomycin C and prostaglandin analogues are medications to definitely avoid during pregnancy, he said.

The best approach is avoidance of glaucoma medications during this period, he said.

“You see what happens to pressure when you take them off the medications, monitor the pressure, and see if the optic nerve can tolerate it,” Dr. Rhee said.

Selective or argon laser trabeculoplasty are potential surgical solutions for pregnant patients, he said. If those are not successful, some investigators have suggested cylcophotocoagulation as a good option, Dr. Rhee said. Trabeculectomy without anti-metabolites or post-op anti-inflammatory medication is another procedure to try. Still, the surgical methods have a lower success rate because of the young age of the patients.

“It’s a notoriously difficult area,” he said. By the time the patient has delivered the baby and is nursing, glaucoma practitioners can once again consider how much the patient needs her medications. A switch to bottle feeding for the newborn may be the best option so the patient can resume their medicine, Dr. Rhee said.

Editors’ note

Dr. Rapuano lectures for Alcon (Fort Worth, Texas) and Allergan (Irvine, Calif.). Drs. Davis and Rhee have no financial interests related to their comments. Dr. Sheppard is a consultant for Alcon, Allergan, Bausch & Lomb (Rochester, N.Y.), and various other companies.

Contact Information

Davis: 952-888-5800, eadavis@mneye.com

Rapuano: 215-928-3180, cjrapuano@willseye.org

Rhee: 617-573-3670, DougRhee@aol.com

Sheppard: 757-622-2220, docshep@hotmail.com